|

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: The Battle of the Wilderness Spring of 1864 brought with it renewed campaigning. On May 2nd, Confederate lookouts near their camps in Virginia south of the Rapidan River detected signs of unusual activity in the Union camps across the river. Major General Ulysses S. Grant had come east with the title of Commander of the Armies of the United States and had been promoted to Lieutenant General. Although he would retain Meade as the nominal commander of the Army of the Potomac, for the remainder of the war it would be Grant who actually directed the army’s military operations. On May 4th, Grant put the Army of the Potomac in motion and crossed the Rapidan heading south. He hoped to be able to pass around Lee’s right quickly enough to avoid combat in The Wilderness, and into more open ground, more favorable to his advantages in numbers and firepower. Lee however, wanted to pin Grant down in the thick second-growth forests and thickets where the Federal numerical and artillery advantages would be at least partially neutralized.[1]

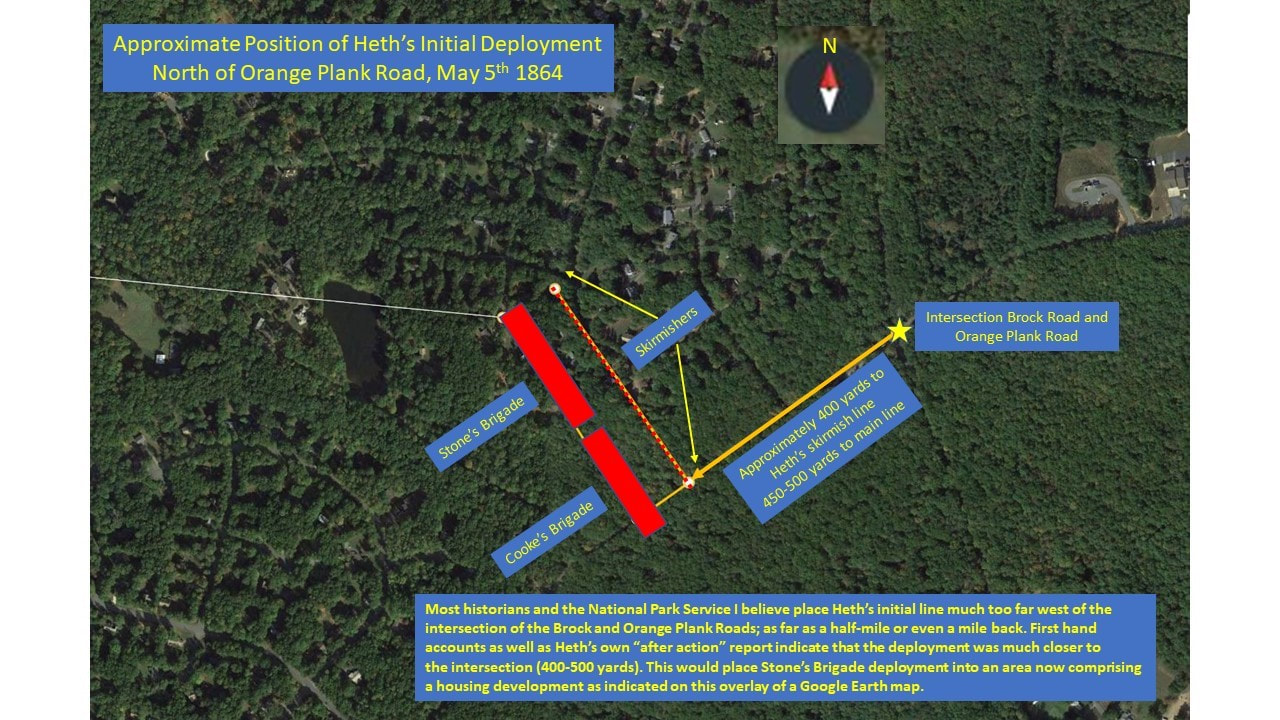

Heth’s Division was in the Third Corps’ vanguard on May 5, 1864 as it marched northeast on the Orange Plank Road to intercept the Army of the Potomac. The corps’ commander, A. P. Hill, was ill and within days would have to temporarily turn over his command to Major General Jubal Early. Joseph Davis, the brigade commander, was also on the sick list and was replaced by his very capable senior colonel, John M. Stone of the 2nd Mississippi. Colonel Stone’s capacity for higher command was very soon to be put to the test.[2] Heth’s Division reached the vicinity of the intersection of the Plank and Brock roads in the early afternoon and found it occupied by units of John Sedgwick’s VI and Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps from the Army of the Potomac. The division fanned out on both sides of the Plank Road, Colonel Stone’s [Davis’] Brigade to the left, Brigadier General John Cooke’s North Carolina brigade in the center astride the road itself, and Brigadier General Henry Walker’s Virginia brigade to the right. Brigadier General William Kirkland’s brigade of North Carolina troops was held in reserve. The Confederates prepared hasty breastworks and prepared to receive the anticipated attack. Stone’s sector covered a frontage of about five hundred feet on the left of the division line, about nine hundred feet north of the Plank Road along the ridge bordering Wilderness Run. Accounts indicate the initial deployment was with the 26th Mississippi on the extreme left, with the 42nd Mississippi to its right. The 55th North Carolina was to the right center of the brigade and the 2nd Mississippi, 11th Mississippi, and 1st Confederate Battalion filled in the area to the left and right of the 55th North Carolina. With Colonel Stone now acting brigade commander, the 2nd Mississippi was placed under the temporary command of Captain Thomas J. Crawford of Company G.[3] Successive Federal assault waves hit Heth’s line as Hancock sent his forces in piecemeal. After two hours of assaults, all of which had been bloodily repulsed, the Union attack crested at about 5:00 p.m. By this point in time, Hancock had finally succeeded in massing his infantry for an effective blow and drove the Confederates back a quarter mile. After another hour of fighting, having withstood seven separate assaults and with no help forthcoming, Stone was about to order what would have almost certainly been a suicidal counter-charge to try and stabilize his front. Finally, about 6:30 p.m. Brigadier General Edward L. Thomas’ Georgia brigade of Wilcox’s Division arrived to relieve Stone’s men who were in the process of preparing to sacrifice themselves to hold the position until nightfall. A counterattack would no longer be necessary. Stone pulled his battered brigade back to regroup in the deepening shadows. After dark, Colonel Stone was ordered to move south of the Plank Road to the right of the Confederate line near Popular Run and about a mile below the Plank Road. Like other regiments in the brigade, the 2nd Mississippi suffered severely in killed and wounded during the first days’ fighting.[4] Hancock’s II Corps attacked again at dawn on May 6th. The attack swept down on the flank of Wilcox’s Division and routed it. Heth’s Division also began to give way. Stone’s Brigade alone held firm while the Federal masses swept past on their left and continued to hammer at their front for two hours. Except for Stone’s Brigade, Heth’s Division was put out of action for the remainder of May 6th.[5] About 6:30 a.m., Longstreet finally arrived with First Corps reinforcements. The Texas Brigade began the counterattack (in the presence of General Lee, himself) with a charge on the north side of the Plank Road and other fresh troops continued to throw back the Federal advance. Thirty minutes later, Stone’s men were relieved and moved to the rear. However, twice later that day, Colonel Stone volunteered his brigade to support Confederate counteroffensives to help stall the Federal advance, including Longstreet's crushing assault into Hancock’s flank ("You rolled me up like a wet blanket..."). When again placed on the defensive, the 2nd Mississippi held its position against continuing Federal attacks until dark.[6] The 2nd Mississippi, as well as the other units in Davis's (Stone's) brigade paid a high price in killed and wounded at The Wilderness.[7] [1] Gordon C. Rhea, The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5-6, 1864 (Baton Rouge, 1994), pp. 49-54; O.R., 36, pt. 1, p. 1028. [2] Ibid., p. 96; Rhea, Wilderness, p. 193; Robert Garth Scott, Into the Wilderness with the Army of the Potomac (Bloomington, 1985), p. 27. [3] O.R., 36, pt. 1, pp. 189-190, 319; Scott, Wilderness, p. 73; John Michael Priest, Nowhere to Run: The Wilderness, May 4th & 5th, 1864 (Shippensburg, 1995), p.147; Confederate Veteran, vol. IX (1901), p. 165. Robert F. Ward in Lee’s Sharpshooters by W. S. Dunlop (Morningside House, Inc., 1982), pp. 368-369. There is still apparently some confusion as to the exact disposition of Stone’s regiments. Contemporary accounts also put the 11th Mississippi on the extreme left of the brigade. Since the Twenty-sixth was later pulled out of line and moved to the opposite flank, and the Forty-second became separated from the rest of the brigade during the fighting, the Eleventh might have ended up on the left end of Stone’s line at some point in time. [4] O.R., 36, pt. 1, pp. 190, 320, 951-952; Scott, Wilderness, pp. 87-88; Rhea, Wilderness, pp. 232-233. Among the wounded, for the second time during the war, was the author’s great-grandfather. He was hit in the left shoulder and lower jaw by one or more Minié balls in the fighting north of the Orange Plank Road at The Wilderness on May 5th. Although he survived the war, the wounds left him permanently disabled. His days as a member of the 2nd Mississippi were over. [5] Scott, Wilderness, p. 115; Supplement, 6, pt. 1, p. 706. [6] O.R., 36, pt. 1, p. 1055; Scott, Wilderness, p. 146, 165; Rhea, Wilderness, pp. 301-302, 356-357, 400. [7] Davis's Brigade suffered horrendous losses at Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, Davis's Brigade mustered about 2,300 men in four regiments (2nd, 11th, and 42nd MS and 55th NC). By the time of the Battle of the Wilderness, the brigade had added the 26th MS and the 1st Confederate Battalion to it's ranks and still only numbered about 1,690 men. The 2nd Mississippi numbered between 280-285 effectives, down from the 492 it brought into action at Gettysburg on July 1st. By the end of the two-days fighting at the Wilderness, the brigade would have suffered some 586 casualties (killed, wounded, captured and missing). The 2nd Mississippi lost 110 men of that total.

2 Comments

Jimmy Bryson

10/22/2019 07:29:12 pm

In you comment section about the Battle of the Wilderness, you mentioned the 2nd MS paid a high price in killed and wounded in the battle and then you footnoted the list. In that list in a William D (Drayton) Bryson that was wounded and furloughed for 60 days. In the Sam Agnew Diary, he states that Drayton was home just days before the Battle of Brices's Crossroads. He would have been there during the battle with his father's home on the edge of the battlefield and his Grandmother's home within the battlefield. Both homes were used as hospitals during the battle and four of the Confederate soldiers killed were buried in a private graveyard on Drayton's Grandmother's land. Drayton still has a living Granddaughter in Tennessee. Another point, when he was released from prison he had to walk almost all the way home from Delaware and his feet were worn down to the bones and he was crippled for life.

Reply

Michael Brasher

10/22/2019 07:57:15 pm

Jimmy,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Michael R. BrasherBesides being the self-published author of Civil War books, I am the great-grandson of Private Thomas Benton Weatherington, one of the 1,888 Confederate soldiers from northeast Mississippi that served in the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. A lifelong Civil War buff, I grew up near the Shiloh battlefield in West Tennessee. I received my MA in Civil War Studies from American Military University. I also hold degrees in Electrical Engineering and an MBA which I draw upon to help shape my own unique approach to researching and writing Civil War history. As former president and co-founder of InfoConcepts, Inc., I was the co-developer of the American Civil War Regimental Information System and Epic Battles of the American Civil War software. I developed and maintained the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment website from 2002 until 2015 and now maintain the 2nd Mississippi Facebook page. I am also writing a regimental history to be released in the near future. I am a retired Air Force officer and now reside in Huntsville, Alabama. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed