|

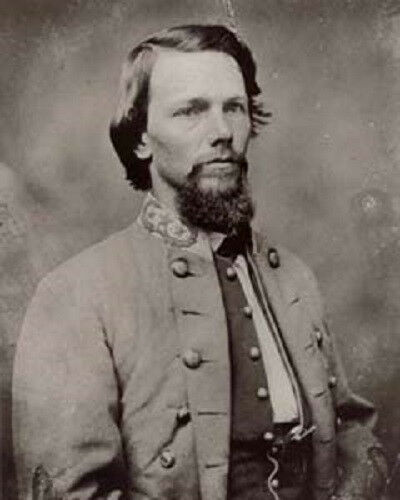

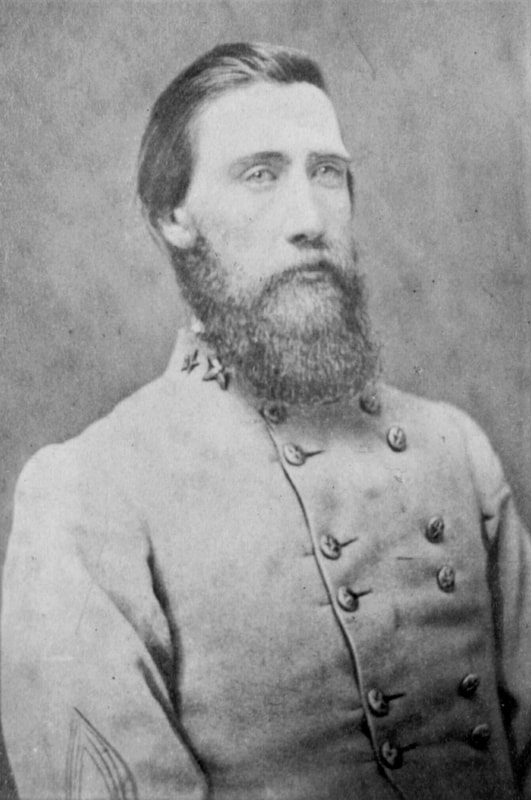

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: South Mountain and Antietam  Colonel Evander Law Colonel Evander Law The usually cautious McClellan’s newfound sense of aggressiveness was fostered by the discovery on September 13th of a copy of Lee’s campaign plans outlining the division of the Confederate army and routes of march. On September 14th, the Army of the Potomac engaged the Southern forces detached to guard passes through South Mountain, Maryland. Responding to the seriousness of the threat, Longstreet ordered Hood back from Hagerstown via Boonsboro to reinforce the Confederate defenders at Fox’s Gap. Immediately upon arriving, Hood deployed Law’s Brigade and his Texans, and in a counterattack, drove the Federals back at bayonet point. The 2nd Mississippi suffered approximately 17-18 casualties, mostly wounded and captured.[1] At nightfall, Lee fell back from the gaps with Hood’s Division acting as rear guard. Although a more prudent commander would have probably fallen back across the Potomac into Virginia, Lee chose to stand and fight. He concentrated his forces in a strong defensive position on the west side of Antietam Creek around the village of Sharpsburg, Maryland. He wanted to maintain this position to block any attempted advance by McClellan and allow time to complete the capture of Harpers Ferry and its garrison.[2] Tired and hungry, the men of the 2nd Mississippi found it necessary to again advance against the Federals at dusk on the evening of September 16th. Elements of the Army of the Potomac had crossed Antietam Creek north of Lee’s army and were moving into positions opposite the Confederate left flank. Hood was ordered into the East Woods, a small woodlot which was being infiltrated by Federal skirmishers. Law’s Brigade, in skirmish order just north of the East Woods, was suddenly met by a reconnaissance party of the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves (“Bucktails”). The Bucktails, with their Sharps breechloading rifles, used their enhanced firepower to turn the slow withdrawal of Law’s skirmishers into a stampede as they neared the edge of the woods. Luckily, the 4th and 5th Texas arrived to hit the Pennsylvanians simultaneously from the west and south, supported by a section of howitzers from Stephen D. Lee’s artillery battalion. By 8:00 p.m. however, most of Hood’s units had fallen back to the West Woods for the night. As darkness fell, Law’s Brigade soon came under Federal artillery fire from the batteries to their right on the other side of Antietam Creek.[3] As night approached, the men lay in the West Woods, facing north while the Union heavy guns fired down the length of their lines from the east. Luckily, most of the shots fell just in front or rear of the Confederate positions. However, the colonel of the 11th Mississippi, Phillip Liddell, was struck in the torso by a bursting shell fragment and would die two days later.[4] Sometime after midnight, Hood’s men were relieved and allowed to get some rest and food. Other than a half ration of beef and some green corn, they had not eaten for three days. As most of the men wearily returned to their original positions near the Dunker Church, details from each company were sent to forage for food and prepare a morning meal.[5] The men of the 2nd Mississippi were awakened on the morning of September 17th while it was still dark. Although Hood had persuaded General Lee to allow the division to stay in reserve long enough for the men to eat their long-overdue meal, McClellan’s battle plans did not cooperate. Shells began to fall near the Dunker Church in preparation for a Federal assault on the Confederate left. Law was forced to order the still-hungry men to fall into ranks and prepare for battle.[6] Somewhat after 6:00 a.m., Colonel Law moved his brigade in columns east across the Hagerstown Pike, where it turned north and deployed in a single battle line. The 2nd Mississippi under Colonel Stone anchored the extreme left of Law’s line, while next came the 11th Mississippi, 6th North Carolina and 4th Alabama on the extreme right. To the left of the 2nd Mississippi the Texas Brigade was similarly deployed in line, with the 1st Texas on the right of the brigade. Law’s men advanced into the Miller Cornfield in a generally northerly direction, loading and firing as they went, except for the 4th Alabama, which moved by the right flank down the Smoketown Road toward the East Woods. The veteran fighters of the 2nd and 11th Mississippi and the 6th North Carolina savagely drove the Federals out of the Cornfield (probably upset at having their long-anticipated breakfasts interrupted). They then reformed along a rail fence at the northern edge of the field, continuing to fire at Federal batteries and infantry units coming onto the scene. At one point, the Confederate line rose and fired at a mere thirty feet distance into the 4th and 8th Pennsylvania Reserves, panicking them, which in turn, panicked the 3rd Pennsylvania Reserves in their rear. As the Federals regrouped and additional reinforcements arrived, however, Hood’s men saw they could not continue to hold their position without help. Union soldiers were infiltrating the gap that had developed between the 6th North Carolina’s right flank and the 4th Alabama’s left, slowed by its advance into the East Woods. The men had to fall back. As Law’s men withdrew, the northern border of the Cornfield along the fence was marked by a long precise, row of Mississippians, stuck down where they stood by one terrible fire.[7] Hood’s punishing counterattack into the Miller Cornfield had saved the Confederate left, but at a terrible cost. As the survivors retired behind the Dunker Church, they found only about 700 unwounded men of approximately 2000 in the division who had advanced at dawn. For expediency, the remnants of Hood’s two brigades were reorganized in the field as two regiments. Despite the losses however, these veteran soldiers recovered sufficiently to be used to gather up stragglers from other units. By 1:00 p.m., Hood had been resupplied with ammunition and the men were ready for combat once again, but the main fighting had moved further down the line. The Federals showed no further interest in trying to advance against the Confederate left for the remainder of the day.[8] After the war, on June 1, 1876, Colonel Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin wrote Colonel (then Governor) Stone a letter that mentioned the fight at Antietam. It reads in part, “We fought the Second Mississippi in the corn field in front of the Dunkark [sic] Church at Antietam. They drove us, and we barely saved by hand a battery of six twelve-pound howitzers, planted in front of some hay stacks. You will remember this place well, if your [sic] are Col. Stone of that Regiment.” This would not be the last time the 2nd Mississippi encountered the 6th Wisconsin in battle. The regiment reported heavy losses of 27 killed and 127 wounded at Antietam. Its strength is not known with certainty, but may have numbered about 300 effectives at the start of the battle (most Southern regiments were much reduced by straggling on the march north into Maryland). Among the wounded were Colonel Stone, Lieutenant Colonel David Humphreys and Major John Blair, all the regiment’s field officers.[9] [1] CMSR. [2] Johnson and Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders, vol. 2, p. 603; O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 839, 922-923; pt. 2, pp. 609-610; Priest, Before Antietam, p. 218. [3] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 937; Priest, Antietam, pp. 15-17, 19-23. [4] Ibid., p. 18. Davis, Leaves in an Autumn Wind, p. 285. [5] Murfin, Bayonets, p. 210. [6] O.R., 19, pt. 1, p. 923, 937. [7] Priest, Antietam, pp. 52, 55-56, 61-62, 64-65, 68-70; Sears, Landscape, p. 213. [8] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 925, 938; Sears, Landscape, p. 276. [9] Rietti, Military Annals of Mississippi, p. 36; Rowland, Military History of Mississippi, p. 47. One of the wounded was the author’s great-grandfather, Private Thomas Benton Weatherington, Company H, 2nd Mississippi. His pension application says he was wounded in both legs on September 17.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Michael R. BrasherBesides being the self-published author of Civil War books, I am the great-grandson of Private Thomas Benton Weatherington, one of the 1,888 Confederate soldiers from northeast Mississippi that served in the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. A lifelong Civil War buff, I grew up near the Shiloh battlefield in West Tennessee. I received my MA in Civil War Studies from American Military University. I also hold degrees in Electrical Engineering and an MBA which I draw upon to help shape my own unique approach to researching and writing Civil War history. As former president and co-founder of InfoConcepts, Inc., I was the co-developer of the American Civil War Regimental Information System and Epic Battles of the American Civil War software. I developed and maintained the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment website from 2002 until 2015 and now maintain the 2nd Mississippi Facebook page. I am also writing a regimental history to be released in the near future. I am a retired Air Force officer and now reside in Huntsville, Alabama. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed