|

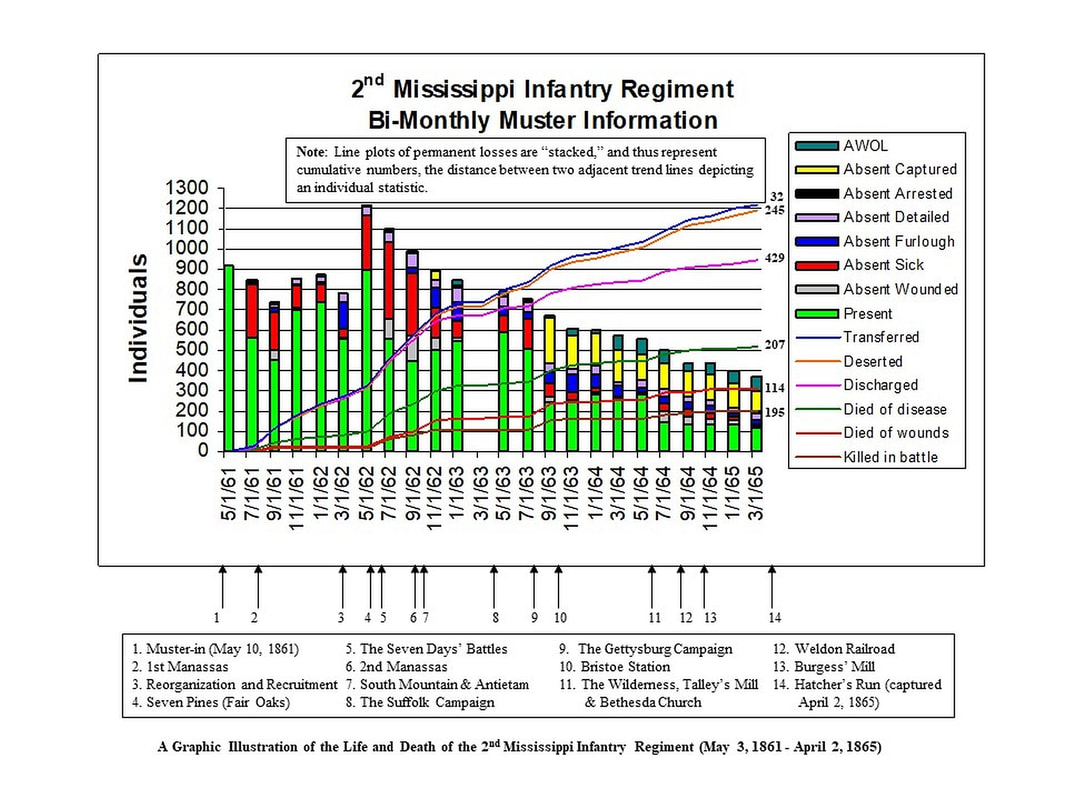

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: Post-Gettysburg Recovery and Bristoe Station The Gettysburg Campaign was the last major action of 1863 for the bloodied 2nd Mississippi. However, the regiment did suffer some additional casualties at Bristoe Station in October when A. P. Hill unwittingly sent his troops into a cleverly set Federal trap. And, although the men anticipated a fight at any time, the Mine Run Campaign in November and December resulted in little actual fighting and few casualties for the 2nd Mississippi.

The regiment spent the winter of 1863-64 in Virginia. As the months went by, the unit regained some of its former strength in numbers. Many of the Gettysburg wounded recovered sufficiently to rejoin the regiment, some prisoners were exchanged, and a handful of new recruits and transfers arrived. By March 1, 1864 the regiment mustered about 260 effectives.[1] On March 24, 1864, two units from the Army of Tennessee, the 26th Mississippi and 1st Confederate Battalion, were ordered east to strengthen Davis’ weakened brigade.[2] [1] CMSR. [2] O.R., 32, pt. 3, p. 676; Crute, Units), pp. 66, 181; Sifakis, Compendium: Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and the Confederate Units and the Indian Units, pp. 180-181, and Mississippi, pp. 114-115; InfoConcepts, Inc., Volume I – the Confederates, computer database software; Rowland, Military History of Mississippi, pp. 116-121, 129. It is unclear as to the exact time these two units joined Davis’ Brigade, but it was prior to the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5-6, 1864. Even though many order of battle listings do not identify these two units as part of Davis’ Brigade, (including the O.R. lists), their presence was clearly noted in first-hand accounts of the fighting. Three companies of the six-company 1st Confederate Infantry Battalion came from the disbanded 2nd Alabama Infantry Regiment. There was one company each from Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee. Many of the men of the 26th Mississippi came from the same part of the state as the 2nd Mississippi.

1 Comment

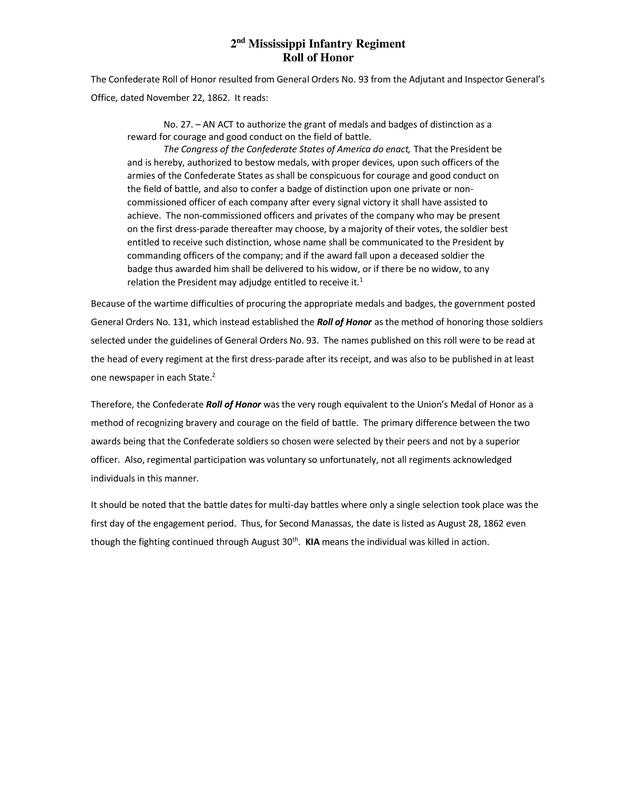

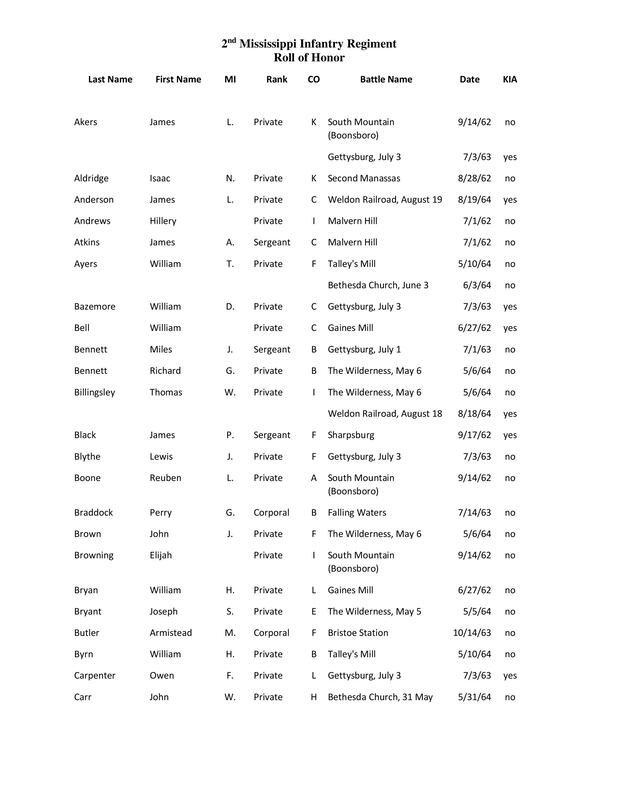

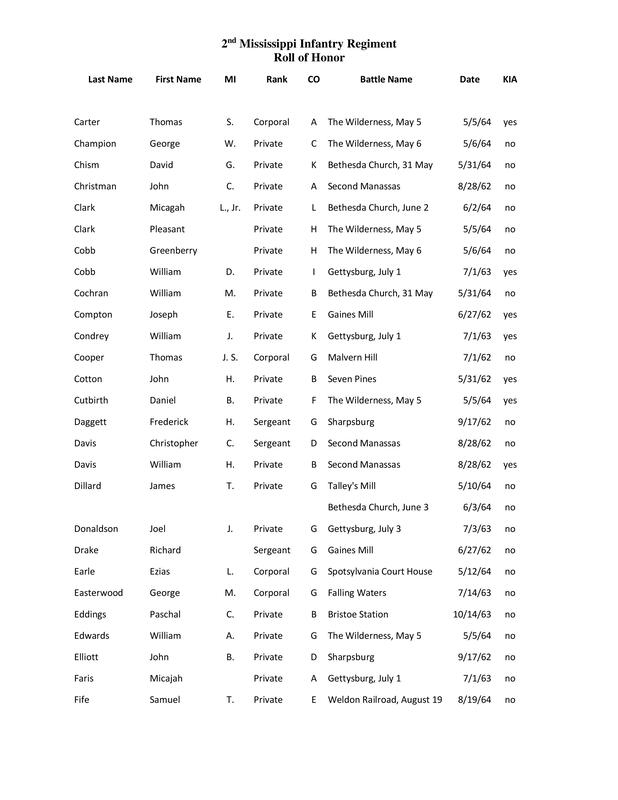

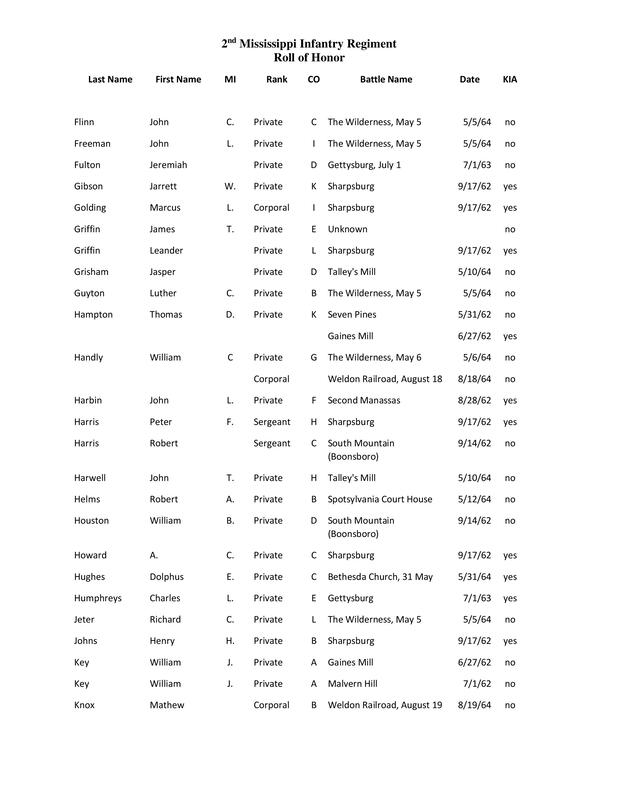

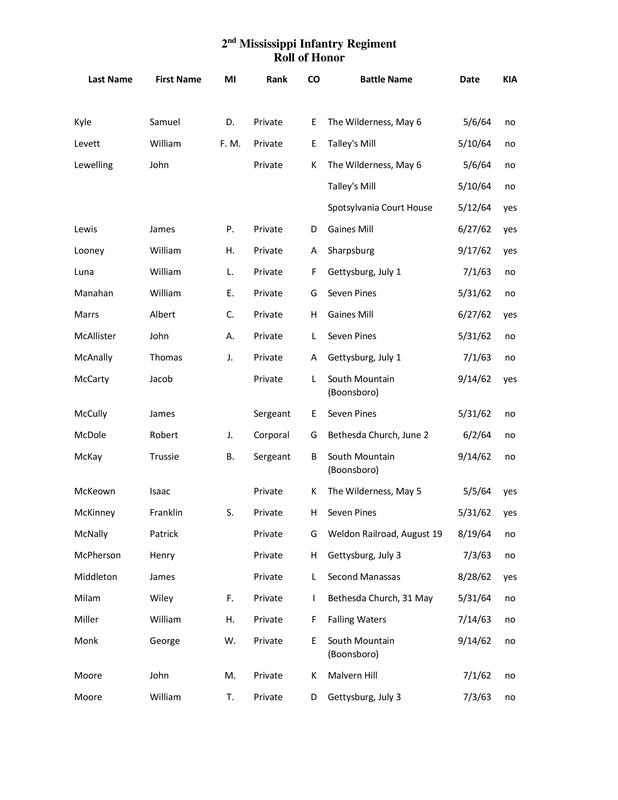

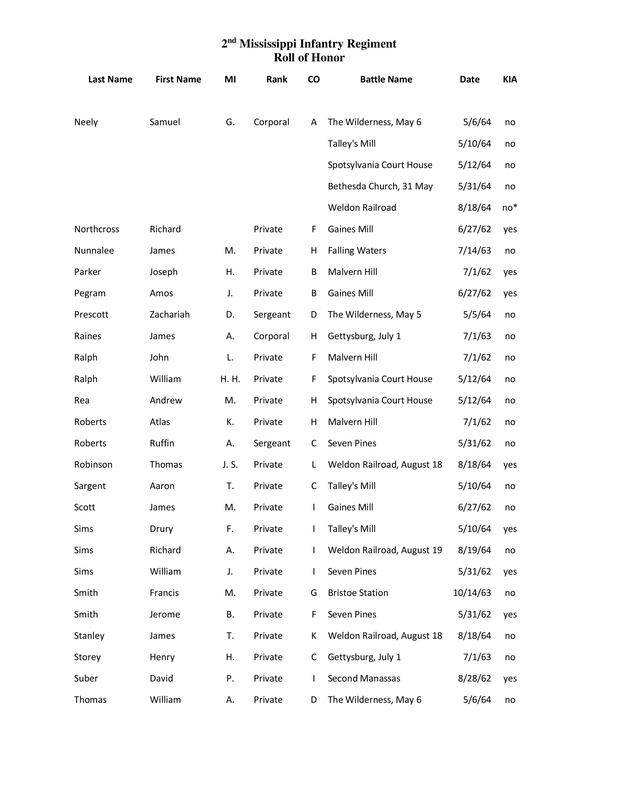

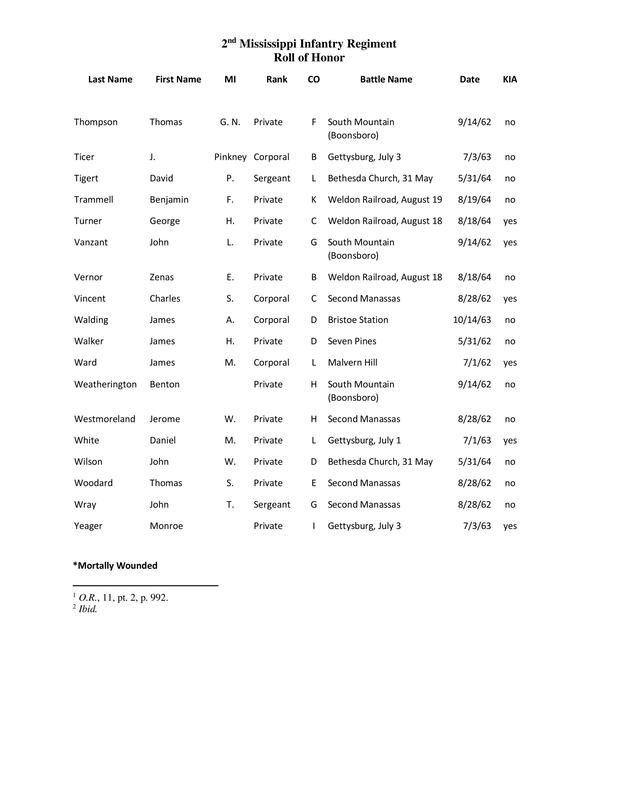

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: The Confederate Roll of Honor: 2nd Mississippi The 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment had more individuals named to the Confederate Roll of Honor – 141 individuals with 153 listings – than any other regiment in Confederate service. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: The Gettysburg Campaign: Part IV: The Retreat: Williamsport and Falling Waters The 2nd Mississippi and the rest of Davis’ Brigade were not quite finished fighting even after Lee began his retreat from the battlefield. Upon arriving at Williamsport, Maryland on July 6th, Lee set up a defensive perimeter while constructing bridges over which to cross the Army of Northern Virginia back into Virginia. Major Belo of the 55th North Carolina described the situation at Williamsport in his memoirs:

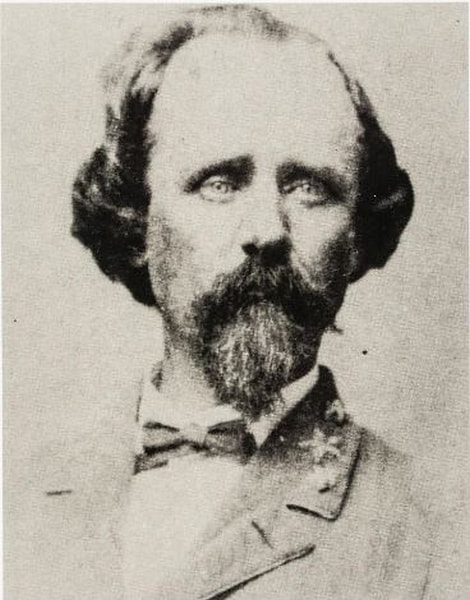

"On arrival at Williamsburg [Williamsport], on the river, I found the whole wagon train of General Lee’s army held by high water. A portion of the Federal cavalry made a demonstration with some artillery and shelled the train. Colonel [J. M.] Stone of the Second Mississippi, Major [R. O.] Reynolds of the Eleventh, and myself, went around and got all the able-bodied men to take places in the trenches in front of us. Besides these, numbers of teamsters and detailed men, soldiers retiring for sick leave, furlough, etc., were drawn up, and checked the Federals and saved the wagon train."[1] Acting as Lee’s rear guard and covering the withdrawal at Falling Waters, Heth’s battered division was attacked by two Federal cavalry divisions on July 14th in the early morning hours. At Williamsport, the regiment suffered an additional three casualties (one mortally wounded and captured, one wounded and captured, one wounded). At Falling Waters where the 2nd Mississippi anchored the extreme right flank of the rear guard perimeter on July 14th, another 20 casualties were inflicted on what remained of the regiment. Two men were killed, six wounded (two of these were also captured), and fourteen, including two of the wounded, were taken prisoner. If the casualties from July 1-5 are added to those from July 6-14, the 2nd Mississippi lost between 411-434 men of an estimated 492 (between 84%-88% of its strength on July 1st).[2] Along with other units belonging to Heth’s Division, the 2nd Mississippi had the dubious distinction of participating in both the opening and closing combat actions of the Army of Northern Virginia during the Gettysburg Campaign. [1] Boatner, Civil War Dictionary, pp. 273-274; Stuart Wright, ed., Memoirs of Alfred Horatio Belo, Masters Thesis, (Winston-Salem, 1980), p. 55. One of these men was the author’s great-grandfather. Still apparently recovering from wounds suffered at Antietam, he missed the fighting at Gettysburg where his older brother was killed, but was present with the army and pressed into action at Falling Waters during Lee’s retreat. [2] CMSR. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: The Gettysburg Campaign: Part III: Pickett's Charge On July 3rd, Davis’ decimated brigade was placed in line in Heth’s Division (now commanded by Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew due to a disabling head wound received by Heth on July 1st). Colonel John M. Brockenbrough’s Virginia brigade was deployed on the left. Next came Davis, then Pettigrew’s Brigade (commanded now by Colonel James K. Marshall of the 52nd North Carolina), and Archer’s Brigade (now under the leadership of Colonel Birkett D. Fry of the 13th Alabama, with Archer’s capture on July 1st). Archer’s Brigade would dress on the left of Pickett’s Division during the advance. Davis formed his men with the 55th North Carolina on the right, followed by the 2nd and 42nd Mississippi with the 11th Mississippi on the brigade left. The four regiments in the brigade may have now numbered as few as 1,000 men. The 11th Mississippi, which saw no action on July 1st, was probably the largest regiment. The 2nd Mississippi, now numbering only 60 muskets* – less than a full-strength company – was undoubtedly the smallest [*Author’s note: other accounts put the survivors of the 2nd Mississippi as high as 200 rank and file in line on July 3rd. Based upon the subsequent reports of the fighting and numbers involved during the retreat from Gettysburg, I tend to believe the survivors in the regiment numbered closer to the 200 number than the 60 muskets referenced by Vairin]. Bearing another set of colors during the charge was Color Sergeant Christopher Columbus Davis, who had been ill on July 1st.[1]

Following a massive Confederate artillery barrage, which unfortunately did not have the desired effect of driving the Union batteries from their positions on Cemetery Ridge, the Southern infantry were moved into position. When the order was given to advance, the gray lines swept forward in magnificent array. The Southern cannoneers ceased firing and cheered the infantrymen as they advanced beyond the guns. Pettigrew’s division emerged from the woods with banners flying in the cannon smoke. Davis recalled, “the order to move forward was given and promptly obeyed. The division moved off in line, and, passing the wooded crest of the hill, descended to the open fields that lay between us and the enemy.” Breaking into the sunlight, Davis’ men realized the magnitude of their task. Vairin wrote in his diary that Davis’ Brigade “joined in making the last grand charge which was so disastrous to our army.”[2] The lines advanced across the fields in perfect order. Awed by the spectacle, Federal gunners did not contest the advance at first. Davis later reported, “Not a gun was fired at us until we reached a strong post and rail fence about three-quarters of a mile from the enemy position, when we were met by a heavy fire of grape, canister, and shell, which told sadly upon our ranks.”[3] Under the deadly rain of shot and shell, the Southern infantry pressed forward and Davis proudly reported, “Under this destructive fire, which commanded our front and left with fatal effect, the troops displayed great coolness, were well in hand, and moved steadily forward, regularly closing up the gaps made in their ranks.” The Confederate lines swept over several fences and quickly restored their alignment each time. The artillery fire, however, became more telling, and as they neared the Emmitsburg Road, Brockenbrough’s small Virginia brigade began to waver. The commander of the 8th Ohio Infantry Regiment, west of the Emmitsburg Road, saw an opportunity to take the Confederate line in flank and poured a heavy fire into Brockenbrough’s left. The Virginians broke and fled to the rear, leaving Davis’ Brigade, and particularly the 11th Mississippi, exposed in turn. The unopposed troops on the Federal right flank overlapping Davis’ line in that direction wheeled left and poured a deadly enfilade fire into the Mississippians’ already depleted lines. Still the men pressed on, and as unit cohesion was lost, they continued in small groups and individually toward the Federal line. Davis reported that as his men neared the stone wall, they “were subjected to a most galling fire of musketry and artillery, that so reduced the already thinned ranks that any further effort to carry the position was hopeless and there was nothing left but to retire to the position originally held, which was done in more or less confusion.”[4] Confederate casualties were appalling. Thousands of men were killed or wounded and left upon the field as remnants of Pickett’s, Pettigrew’s, and Major General Isaac R. Trimble’s commands sought shelter on Seminary Ridge. Davis’ Brigade suffered greater losses than any other Confederate brigade at Gettysburg. As remnants of the wrecked regiments regrouped west of Seminary Ridge, Davis took stock of the magnitude of his losses and wept. All the field officers were casualties. The losses among the junior officers were staggering. The 2nd Mississippi, which entered Pickett’s Charge with only 60 men, now counted only one unwounded survivor.[5] At the height of the fighting, as Lieutenant Colonel David Humphreys led the remnant of his proud regiment near the Brian Barn on Cemetery Ridge, Sergeant Davis, the gallant color-bearer of the 2nd Mississippi, was shot down, along with his colors. Although severely wounded, he managed to tear the colors from the staff and hide them under his body. Lt. Col. Humphreys would die in the assault. As fate would have it, Lieutenant Colonel Dawes decided to take a riding tour of the scene of the carnage following Pickett’s Charge. Dawes slowly worked his horse among the dead and wounded bodies on Cemetery Ridge near the Angle, where the grand assault had climaxed. Just then, one of the wounded men in gray caught sight of Dawes, who was still in possession of the captured colors of the 2nd Mississippi from the fight at the Railroad Cut on July 1st. The wounded man cried out in a faint voice, “You have got our colors, let me see them.” Hearing the man’s appeal, Dawes moved toward the wounded Confederate. As he approached, he noted the man was badly, possibly mortally, wounded. He dismounted and knelt beside the wounded sergeant. “This man and I had quite an interview” recalled Dawes, during which time the Confederate sergeant identified himself as a color-bearer in the 2nd Mississippi Infantry. “The poor fellow was quite affected to see his colors,” noted the 6th Wisconsin commander, “and I did all I could to comfort him.” The men talked of the action on July 1st, after which Dawes had to leave. Although he later wrote that “I did all in my power to secure for him aid and attention,” he noted with regret that “I do not know whether this sergeant survived his wound.”[6] The unidentified sergeant must have been Davis.[7] The 2nd Mississippi entered the battle at Gettysburg with an estimated strength of 492.[8] It reported 232 killed and wounded, but did not separately report any numbers for those captured or missing. At least 88 officers and men of the regiment were taken prisoner at the Railroad Cut on July 1st. The compiled service records show for the period of July 1-5, that 49 men were killed, 114 wounded and not captured, 110 wounded and captured, and 138 captured and apparently unwounded. Thus, the total casualty count comes to 411 of the 492 men present at the start of the battle. Some uncertainty exists in these numbers, however, because 28 records only exist as Federal prisoner of war documents. An additional 43 records confirm only that an individual was admitted to a Confederate hospital in Virginia with a battle wound during the period immediately after the Gettysburg campaign and corroborating information is not provided in the company muster records. If we assume that 1/3 of each of these two groups are misidentified, the number of total Gettysburg casualties comes down to 388. Thus, if Busey’s and Martin’s strength estimate is correct, the 2nd Mississippi suffered losses of in the range of 79%-84% (killed, wounded and captured).[9] Actually, a casualty rate of 80% agrees well with the single company that actually reported its strength at the battle. Company B reported its strength at 66 “aggregate” on July 1st, and had suffered 53 casualties by the close of July 3rd. If indeed only one unwounded member of the regiment returned from Pickett’s Charge, obviously not all 66 men present of this company were in the fight. The situation must have been similar in the other companies making up the balance of the regiment. This would leave between 81-104 men that were apparently unengaged but present during the battle (perhaps detailed to non-combat support activities).[10] [1] O.R., 27, pt. 2, p. 650. Terrence J. Winschel, “The Colors are Shrouded in Mystery.” The Gettysburg Magazine, January 1992, 77-86. Howard M. Madaus, Personal Conversation, May 12, 1998. There is much controversy concerning the origins of the colors borne by Davis on July 3rd. Some accounts – including those of the Bynum brothers who returned the flag to the Mississippi state archives – say the new set of colors was issued by the ANV Quartermaster’s Department on July 2nd with “Gettysburg” already stenciled as a battle honor [Winschel]. Howard Madaus, probably the expert when it comes to Confederate battleflags, says that was simply not possible. He insists that any colors carried by Davis would have had to come from the regimental baggage, probably an older set of previously issued colors. The set of colors with “Gettysburg” would not have been issued until August 1863 according to Madaus (as an aside, this new set of colors was never surrendered by the regiment. At Hatcher’s Run on April 2, 1865 where most of the regiment was surrounded and captured, during the Federal breakthrough, the flag was torn from its staff by Private N.M. Bynum and hidden through his confinement at Fort Delaware. It was later returned to the Mississippi State Archives in 1916). Madaus insists however, that Davis could not have been carrying this flag on July 3rd at Gettysburg. Winschel is convinced otherwise. Based upon the evidence, this author tends to agree with Madaus. Many years had passed since Hatcher’s Run and the Bynum brothers returning the flag in 1916. Memories may have faded over time. Additionally, it would be extremely unusual for only the 2nd Mississippi to be issued replacement colors lost the previous day, when the other regiments in a similar situation had to wait until the ANV Quartermaster issue in August 1863 for replacements. If the Hatcher’s Run colors were not carried by Davis on July 3rd, the fate of the set of colors he did carry is now lost to history. [2] O.R., 27, pt. 2, p. 651; Terrence J. Winschel, “Part II: Heavy Was Their Loss: Joe Davis’s Brigade at Gettysburg.” The Gettysburg Magazine, July 1990, 81; A.L.P. Varian Diary. [3] O.R., 27, pt. 2, p. 651. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid.; A. L. P. Vairin Diary. [6] Rufus R. Dawes, Service With the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Dayton, Ohio: Morningside, 1996), pp. 160, 366-67. [7] According to Winschel’s “The Colors are Shrouded in Mystery,” Davis, with the hidden colors, was taken prisoner at Gettysburg, took the Oath of Allegiance, and, as a “Galvanized Yankee,” deserted the Federal army and made his way back to the 2nd Mississippi with the colors sometime in 1864. As noted previously, Howard Madaus insists that, although Davis may have done exactly that, the colors with which he returned were not the colors carried at Hatcher’s Run and sent to the Mississippi State Archives in 1916. Following the war, Dawes attempted to learn the identity of the man with whom he had spoken on July 3rd. Following a published newspaper appeal, D. J. Hill wrote back to Dawes that he had been a member of the 2nd Mississippi and had known Davis. He informed Dawes that Davis recovered from his wounds and survived the war, only to commit suicide a year or so after it ended. [Hill to Dawes, Sept. 12, 1893, Rufus Dawes Letters, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi] [8] John W. Busey and David G. Martin, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg (Hightstown, 1986), pp. 175, 290 [9] Ibid. The 492 number probably better represents the “aggregate present” classification that is sometimes used to include noncombatants or detailed men in the total. For example, Company B reported 66 “aggregate” present on July 1st, and by the close of July 3rd, 53 were casualties. Some of these 13 men who were not casualties were not on the “firing line” during the battle, but were probably detailed to support duties. [10] CMSR, roll 111. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: The Gettysburg Campaign: Part II: The Color Episode of the 149th Pennsylvania Although battered, the spirit of the regiment was not broken. Later during the afternoon of July 1st, Colonel Stone noticed a stand of Federal colors that had been advanced well to the front of the Union line near a pile of rails. Lieutenant A. K. Roberts of Company H volunteered to lead a party consisting of himself and four men from the 2nd Mississippi in an attempt to capture the enemy colors. The colors belonged to the 149th Pennsylvania Infantry, and they had sent their color party forward as a ruse to draw the fire of Confederate artillery batteries away from enfilading their main line. As Lieutenant Roberts’ squad surprised the Pennsylvanians near the fence railings, a hand-to-hand struggle ensued. Lieutenant Roberts, less heavily encumbered than the other men and athletically inclined, neared the rail pile first, but to the surprise of the squad, the hidden color guard rose up and killed the Lieutenant. In the confusion that followed, the gun of one of Roberts’ men failed to fire, but he used it as a club and in so doing, stumbled and fell among the rails. When he recovered, he noted two of the Federal color guard were retreating with one of Roberts’ men as a prisoner, while the color bearer was also retreating with his flag. He recapped his gun and fired at the color bearer and broke his leg. He then rushed forward, seized the colors from the wounded Federal and, amid a hail of bullets from the Federal line, brought in the captured colors of the 149th Pennsylvania. This man was Private Henry “Tobe” McPherson, also a member of Company H. Colonel Stone offered McPherson the lieutenancy position created by Roberts’ death, which he declined, but accepted a furlough instead.[1]

The battered survivors of Davis’ Brigade spent July 2nd performing light duties and getting some much-needed rest. Augustus L. P. Vairin of Company B, the O’Connor Rifles, noted his regiment had been “reduced fearfully,” and recorded in his diary on July 2nd, “rested all day – gathering arms.” Hundreds of arms were gathered along with other accouterments such as blankets, canteens, haversacks, and cartridge boxes.[2] Finally in the late afternoon, the men of 11th Mississippi arrived from their wagon train guard detail, helping to somewhat raise the spirits of the men who had escaped the debacle at the Railroad Cut. According to contemporary accounts, the 11th Mississippi mustered about 350 men upon its arrival on the battlefield.[3] In the gathering darkness, the Confederate forces fell back from Cemetery Ridge and Davis’ men bivouacked for the night. “From our Bivouac,” wrote Vairin, “we could see the Battlefield of this day.” A few curious soldiers walked to the edge of the woods where, in the moonlight, they gazed upon the scene of the fighting. A sporadic fire continued in this sector of the field and a few unlucky men of the brigade were hit. One of them was Vairin. He recorded his misfortune with the simple statement, “I was struck in the head with a glancing ball which disabled me for the rest of the day so I did no more that day.”[4] [1] J. H. Strain. “Heroic Henry McPherson,” Confederate Veteran, XXXI (1923): p. 205. J. H. Bassler. The Color Episode of the One Hundred and Forty-Ninth Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers. Paper Read Before the Lebanon County Historical Society, October 18, 1907. CMSR. Noted in his compiled service records "Captured a stand of colors [149th Pennsylvania] on 7/1/1863 at Gettysburg in front of lines. Declined promotion therefor." Private McPherson was killed at The Wilderness on 5/6/1864. He appears on a register of appointments, CSA to Ensign & 1st Lt. Date of appointment: 6/6/1864. To take rank: 5/4/1864 (However, Pvt. McPherson was killed before it could take effect). Other historians [Martin, Gettysburg, July 1, for example] have mistakenly identified the Pennsylvania unit that Roberts and McPherson encountered as the 56th Pennsylvania of Cutler’s brigade. This incident occurred some time after the regiment’s experience near the Railroad Cut, probably after 3:00 p.m. in the afternoon. Additionally, credit has been given by other writers to the 42nd Mississippi or the 55th North Carolina, and even a unit from Daniel’s Brigade for capturing these colors. Lieutenant Strain’s account in the Confederate Veteran rings much truer with respect to the known facts. [2] A.L.P. Vairin Diary, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. [3] Baxter McFarland, “Casualties of the Eleventh Mississippi Regiment at Gettysburg,” Confederate Veteran, XXIV (Nashville, 1916), p. 410-411. Busey and Martin’s careful study, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, concluded, based on incomplete Confederate company muster records of June 30,1863, that the 11th Mississippi numbered 592 effectives on July 1st. This is difficult to reconcile with McFarland’s number of 350, even if the assumption is made that a large number of men were “detailed” or on “extra duty” that day. McFarland detailed strengths and losses by individual company for the 11th Mississippi. [4] A.L.P. Vairin Diary, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: The Gettysburg Campaign: Part I: The Railroad Cut  The Fight for the Colors: Don Troiani Historical Art (Used by Permission) Corporal Francis Waller of the Sixth Wisconsin Infantry struggles with Color Corporal William B. Murphy of the Second Mississippi Infantry for possession of the Mississippi colors at the Railroad Cut at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863 Davis deployed his regiments with the veteran 2nd Mississippi in the center, the 42nd Mississippi on its right and 55th North Carolina on its left. The Southerners pushed across Willoughby Run and advanced up the west face of McPherson Ridge, driving in the enemy skirmishers. Davis’ Brigade was concentrated north of an unfinished railroad as it advanced up McPherson Ridge. The infantry of Davis and Archer steadily drove Buford’s cavalrymen to East McPherson Ridge. As Davis’ skirmishers neared the crest of West McPherson Ridge, they caught sight of a long column of Union infantry crossing the Chambersburg Pike on the run. These men were part of Brigadier General Lysander Cutler’s brigade of Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth’s division in Major General John F. Reynold’s I Corps, Army of the Potomac. Davis’ men immediately engaged the Federal infantry as it deployed into line of battle. The 2nd and 42nd Mississippi regiments hit Cutler “head-on,” while the 55th North Carolina was able to approach the flank and right-rear of the Federals. Colonel Stone brought his regiment face to face with Cutler’s troops and held his men grimly to their task. As the opposing line began to waver, Stone was wounded and command of the regiment passed to Major John A. Blair.[1]

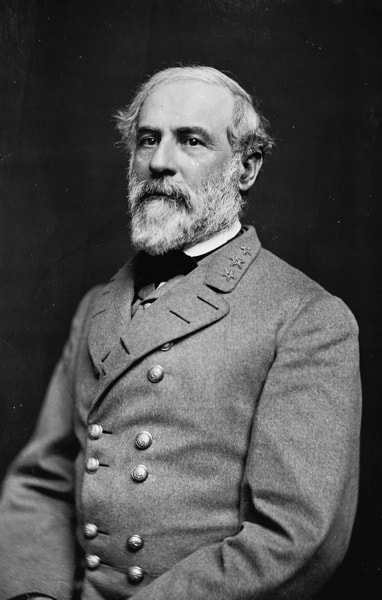

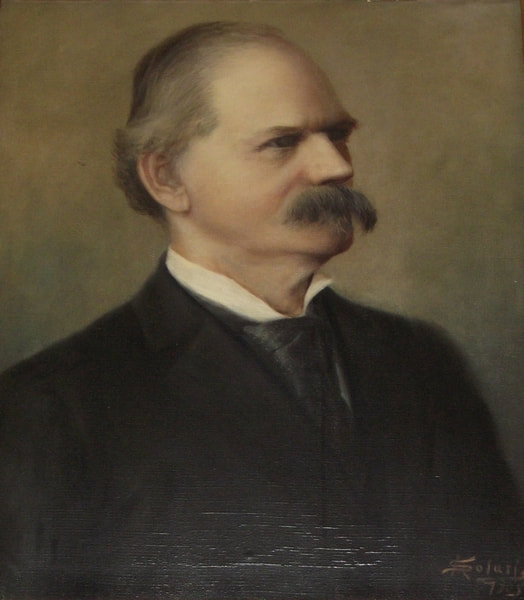

The two regiments forming Cutler’s center and right (the 56th Pennsylvania and 76th New York, respectively), after enduring heavy casualties, were soon put in retreat by Davis’ men. Now the attention turned to the Confederate right where the 42nd Mississippi was locked in bitter combat with Cutler’s leftmost regiment, the 147th New York and the guns of the 2nd Maine Artillery under the command of Captain James Hall. Davis wheeled his regiments toward the Chambersburg Pike to crush the only remaining organized Federal resistance. As the men of the 2nd Mississippi advanced, they could hear the frantic cry of the enemy, “They are flanking us on the right.” One New Yorker, Lieutenant J. V. Pierce, long remembered the Mississippians “pressing far to our right and rear.” As the regiment struggled to cross a rail fence, Pierce wrote, “their colors dropped to the front. An officer in front of the center corrected the alignment as if passing in review. It was the finest exhibition of discipline and drill I ever saw before or since on a battlefield.”[2] The men of the 2nd Mississippi and the North Carolinians surged over the fence and toward the railroad grading when they spotted a section of Hall’s battery retire to East McPherson Ridge and unlimber. The Second loosed a withering volley that crashed into the exposed section and toppled a number of men and horses. Although the Federals were able to bring off both guns, the Confederates caught sight of Hall’s other four pieces retiring from West McPherson Ridge and instinctively charged for them. Several of the Mississippians got among the guns and began shooting and bayoneting the horses to immobilize the battery. Corporal William B. Murphy of Company A recalled, “We poured such a deadly fire into them that they left their [last] piece and ran for life.”[3] Thus, Davis’ initial contact with the Federals had produced substantial results. His brigade had crushed the Union right, captured one gun and limber, and inflicted over five hundred casualties on the enemy. In the excitement of the moment, the Confederates pushed on toward Seminary Ridge in pursuit of Cutler’s routed units. It is at this point that Davis lost control of the situation, allowing the pursuit to become disorganized. Two of his three regimental commanders were down (Stone of the 2nd Mississippi and Colonel John K. Connolly of the 55th North Carolina), and the pursuit was directed more by exuberance than by discipline. The wildly cheering soldiers were oblivious to the approaching catastrophe. Suddenly an unexpected volley of musketry viciously ripped into their flank from the south. The 6th Wisconsin Infantry and Iron Brigade Guard had arrived at the double-quick from the Seminary to try and stem the tide of the Southern advance. Also coming onto the scene was the balance of Cutler’s brigade – the 84th and 95th New York. Bewildered by the deadly hail of missiles, the Mississippians and North Carolinians sought shelter in the nearby railroad cut. Instead of a refuge, it would soon become a trap because, along much of its length the cut was too deep for the men to fire out of. Major Alfred H. Belo of the 55th North Carolina noted in his memoirs, “It occurred to me at this moment that our brigade, being flushed with victory, should charge those regiments [6th Wisconsin, 95th and 84th New York] at once before they could form in line of battle. I told Major [John A.] Blair of the Second Mississippi to have his regiment join me in the charge, but at this moment we received the command to retire through the cut.” Belo further penned, “...if we did not charge them, they would charge us. This proved to be the case.”[4] Davis recognized the seriousness of the situation and later wrote in his after action report, “In this critical condition, I gave the order to retire, which was done in good order, leaving some officers and men in the railroad cut, who were captured, although every effort was made to withdraw all the commands.”[5] Davis’ report however, is a remarkable piece of understatement concerning his brigade’s debacle at the Railroad Cut. While Major Blair was trying to reorganize the jumbled mass of soldiers in the cut, the Federals swept over the post and rail fence lining the pike and charged. The 6th Wisconsin and Iron Brigade Guard were joined on their left by the 84th and 95th New York in the attack. The three Northern regiments suffered heavy casualties from the Southerners’ “fearfully destructive fire,” but were at the edge of the cut and upon the defenders in a matter of moments shouting, “Throw down your muskets!” Major Blair, as the senior officer present, had no choice but surrender or see the men slaughtered. He handed his sword to Lieutenant Colonel Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin. The Federals claimed 7 officers and 225 men from Davis’ three Confederate regiments as prisoners of war.[6] In correspondence with Dawes some thirty years later, Blair would write: "It seems that you did not know of the rail road cut at Gettysburg nor did we. After driving the first line of battle we met and seeing no other troops in our front, (you must have been concealed by an eminence between us) we concluded we would capture Gettysburg without further difficulty or bloodshed and end the war right there. It was therefore, a great surprise to us when we come up to the rail road cut, and a greater one when you swung around on our left and bagged us."[7] One of the most stirring incidents in the history of the 2nd Mississippi and, indeed, in the entire Battle of Gettysburg, occurred in the fierce engagement at the Railroad Cut as the regiment struggled to save its colors. William B. Murphy, the color corporal who was bearing the colors on July 1st, recalled the valiant charge of the 6th Wisconsin and the “desperate struggle” for the colors: "My color guards were all killed and wounded in less than five minutes, and also my colors were shot more than one dozen times, and the flag staff was hit and splintered two or three times. Just about that time a squad of soldiers made a rush for my colors and our men did their duty. They were all killed or wounded, but they still rushed for the colors with one of the most deadly struggles that was ever witnessed during any battle in the war. They still kept rushing for my flag and there were over a dozen shot down like sheep in their mad rush for the colors. The first soldier was shot down just as he made for the flag, and he was shot by one of our soldiers. Just to my right and at the same time a lieutenant made a desperate struggle for the flag and was shot through the right shoulder. Over a dozen men fell killed or wounded, and then a large man made a rush for me and the flag. As I tore the flag from the staff he took hold of me and the color. The firing was still going on, and was kept up for several minutes after the flag was taken from me..."[8] Finally Corporal Frank Waller of Company I, 6th Wisconsin, seized both Murphy and the colors of the 2nd Mississippi. Waller presented the colors to Lieutenant Colonel Dawes who was especially gratified for he noted the 2nd Mississippi was “one of the oldest and most distinguished regiments in the Confederate army.”[9] Those of Davis’ Brigade that were still able, fell back down West McPherson Ridge and across Willoughby Run. Besides the prisoners taken in the Railroad Cut, Davis had left behind several hundred dead and wounded men. He reported his losses as “very heavy.” Heth’s division report noted that “the brigade maintained its position until every field officer save two were shot down, and its ranks terribly thinned.” Heth wrote “from its shattered condition it was not deemed advisable to bring it again into action that day.” Davis’ bloodied regiments, the 2nd Mississippi among them, were kept on the north side of the Chambersburg Pike to collect their stragglers and rest. When the brigade finally went into camp for the night, the only two field officers left were Colonel David Miller of the 42nd Mississippi and Lieutenant Colonel David W. Humphreys of the 2nd Mississippi who had been detached with a large detail to guard wagons. On July 3rd, he would lead the remnant of his regiment, about 60 men, as part of Pickett’s Charge.[10] [1] Ibid., pp. 10-11; Martin, Gettysburg, pp. 101-106; Krick, Failures, pp. 104-107. [2] Glenn Tucker, High Tide At Gettysburg. (Dayton, 1973), p. 114. [3] Winschel, Part I, p. 11; Murphy to Dearborn, June 29, 1900, Papers of E. S. Bragg, State Historical Society of Wisconsin (copy courtesy of Lance Herdegen). [4] Stuart Wright, ed., Memoirs of Alfred Horatio Belo, Masters Thesis, (Winston-Salem, 1980), p. 52 (copy courtesy of Lance Hergeden). [5] O.R., 27, pt. 2, p. 649. [6] O.R., 27, pt. 1, pp. 275-276; Lance J. Herdegen and William J. K. Beaudot, In the Bloody Railroad Cut at Gettysburg (Dayton, 1990), pp. 198, 206-207; Rufus R. Dawes, Service With the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Dayton, 1996), p. 169. Davis’ men made the Federal units pay dearly for their prize at the Railroad cut. The 6th Wisconsin reported losses of 30 killed, 116 wounded and 22 missing (168 total) of 344 engaged. Most of these losses were on the first day of the fighting and must be assumed to have occurred in the battle with Davis’ Brigade. Faring even worse was the 84th New York with 217 casualties of 318 engaged, and, suffering almost as badly was the 95th New York with 115 casualties of 241 engaged [Busey and Martin, p. 239]. The prisoners included Major Blair, Corporal Murphy and 86 other members of the 2nd Mississippi, along with the regiment’s colors (mistakenly listed in the O.R. reports as the colors of the 20th Mississippi). [7] Blair to Dawes, October 23, 1893, Rufus Dawes Letters, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. [8] Murphy to Dearborn, June 29, 1900. [9] Dawes, Sixth Wisconsin, p. 170. Waller would subsequently be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for the capture of the colors of the 2nd Mississippi. [10] O.R., 27, pt. 2, pp. 637, 649-650. One of the dead left behind was Private George W. Weatherington, Company H, 2nd Mississippi – the older brother of the author’s great-grandfather. Previously wounded at Second Manassas, Gettysburg was his first battle since rejoining the regiment. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: The Gettysburg Campaign: Introduction Although Lee was being urged by some factions to consider going west to try and reverse the Confederacy’s fading military fortunes, especially the threatened loss of Vicksburg, he countered that the best hope for independence was to encourage the peace movement in an increasingly war-weary North. The best way to drive down an adversary’s morale was to defeat the enemy army, preferably upon its own soil. To take any other course of action, Lee argued, would result in his becoming penned inside the defensive lines around Richmond. Once that happened, the outcome was inevitable. Thus Lee was given approval on June 10, 1863 to conduct an offensive into Northern territory against Hooker’s army.[1]

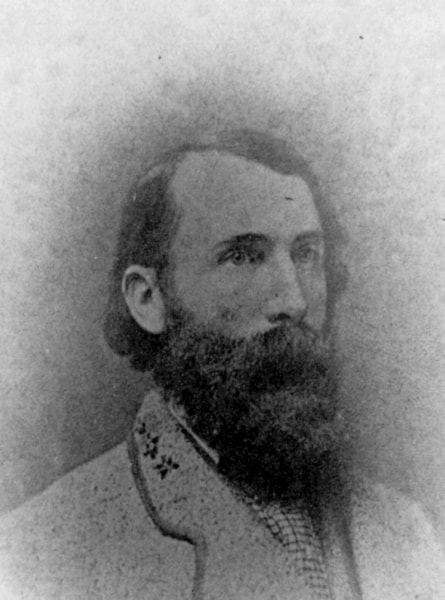

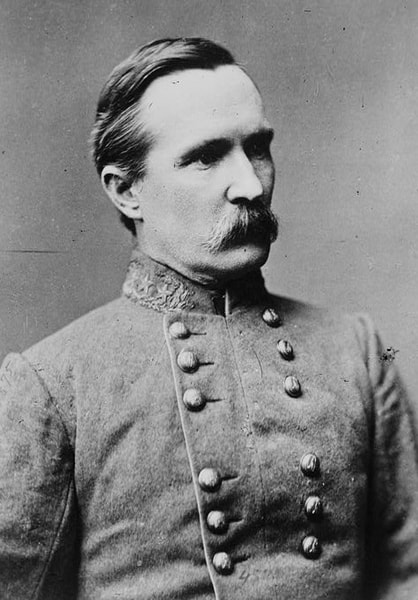

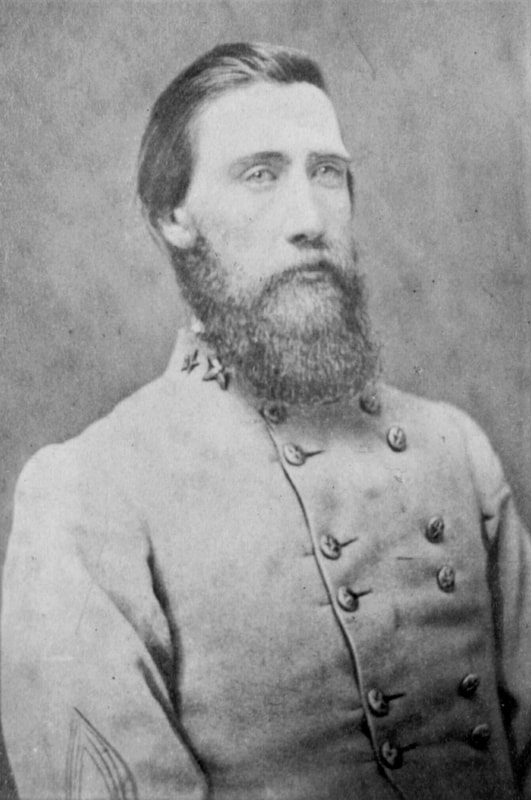

On June 15th the first of Lee’s infantry columns crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, bound for Pennsylvania.[2] Ten days later the 2nd Mississippi, now a part of A. P. Hill’s Corps, crossed the river onto enemy soil. George W. Bynum, one of five Bynum brothers in Company A, noted in his diary, "June 25. Crossed the Potomac by wading and passed through the battle field of Sharpsburg, which was fought September 17, 1862. Much sign of the conflict is visible. The low mounds which cover the bones of those who fell, the furrowed ground, and scarred trees – all speak more plainly than words of that terrible conflict. I saw the ground over which we charged on that memorable occasion and the very spot where I was wounded. Sad, sad thoughts are recalled by again reviewing the old battleground."[3] By the end of June, the regiment was enjoying the abundance of the bountiful Pennsylvania countryside. Early on July 1, 1863, Heth’s Division marched east from Cashtown intent on liberating a supply of shoes earlier reported at the nearby college town of Gettysburg (or so the story goes). The 2nd and 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina regiments of Davis’ Brigade pressed ahead with Heth, leaving the battle-tested 11th Mississippi to guard the division trains at Cashtown. Nobody in the Confederate high command was apparently aware that portions of the Army of the Potomac, now under the command of Major General George Meade, following Hooker’s removal, were rapidly converging on the town from the opposite direction.[4] Brigadier General James J. Archer’s Brigade of Heth’s Division was in the advance and drew first fire at about 7:30 a.m. Seeing Archer deploy a heavy line of skirmishers south of the Chambersburg Pike, the road down which they were advancing, Davis ordered forward skirmishers in a similar manner north of the road. For the next two hours, Archer and Davis would slowly drive Brigadier General John Buford’s Federal cavalry toward Willoughby Run. When the town of Gettysburg finally came into view, Heth ordered Davis and Archer into line to move forward and occupy the town.[5] [1] O.R., 27, pt.3, p. 882. [2] Ibid., p. 442. [3] G.W. Bynum Diary Extracts. Quoted in Confederate Veteran, XXXIII (1925): pp. 9-10. [4] O.R., 27, pt. 2, pp. 637, 649; Robert K. Krick, “Three Confederate Disasters on Oak Ridge: Failures of Brigade Leadership on the First Day at Gettysburg.” The First Day at Gettysburg, (Kent, 1992), 99-104; David G. Martin, Gettysburg July 1 (Conshohocken, 1995), pp. 59-61, 70-71, 86-88. [5] Terrence J. Winschel, “Part I: Heavy Was Their Loss: Joe Davis’s Brigade at Gettysburg.” The Gettysburg Magazine, January 1990, pp. 5-8. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: Detached Duty and the Suffolk Campaign  Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis Following the retreat from Maryland, on November 8, 1862, Special Order 236 directed that the 2nd and 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiments be detached from the army and report to Richmond. There, the two veteran regiments were joined by the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina, two recently organized (May 1862) “green” regiments that had not yet seen combat.[1] These four regiments formed a new brigade under the command of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis, a Mississippian and Jefferson Davis’ nephew. Davis’ Brigade was sent to Goldsborough, North Carolina where the 2nd Mississippi spent a relatively pleasant winter, missing the battle of Fredericksburg, and recovering from some of its campaign losses. Wounded and sick recovered and returned to the ranks, and those taken prisoner were exchanged. However, unlike the previous winter, only a handful of new recruits joined the regiment.[2] With the Federals gaining a beachhead on the Virginia coast south of the James River in February 1863, Lee dispatched two divisions, Hood’s and Pickett’s, to guard the southern approaches to Richmond and Petersburg. Micah Jenkins’ and Davis’ brigades were ordered up from Goldsborough to southern Virginia, where they formed a division under the command of Major General Samuel G. French. Lee ordered Longstreet, on February 18th, to take command of the Southern forces concentrating along the Blackwater River. His orders were to defend Richmond while holding his men ready to return to the main army if needed. Longstreet was also directed to forage for provisions for the undernourished Army of Northern Virginia and, if the opportunity presented itself, to take the offensive against the Federal forces in his front.[3] Following weeks of scouting, foraging and skirmishing along the Blackwater River, the 2nd Mississippi was involved in Longstreet’s unsuccessful siege of Suffolk, Virginia from April 11th to May 4, 1863. Although actual fighting was light, the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina received their “baptism of fire” during a reconnaissance in force upon the Confederate lines by the 99th New York on May 1st.[4] Longstreet had already begun planning the return of his forces to the main army, even as the Confederates were repulsing the Federal probe of the 99th New York. The new commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General Joseph Hooker, was attempting to execute a bold plan to destroy Lee’s army. He already had crossed the Rappahannock River and was threatening Lee’s left flank. Although the divisions of Hood and Pickett began a hurried departure, they did not arrive in time to participate in the Battle of Chancellorsville, often characterized as Lee’s greatest victory, but resulting in tragic consequences for the South. Stonewall Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men on May 2nd, losing an arm and dying of complications from pneumonia a few days later.[5] With Jackson’s death and Longstreet’s return, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia. From the original two-wing structure, three infantry corps were created. Longstreet retained the First Corps, the Second was placed under the command of newly promoted Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, and the new Third Corps was given to the also recently promoted Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill. A new division under Major General Henry Heth, to which Davis’ Brigade was assigned, was also placed in Hill’s Corps. On June 5th the 2nd Mississippi, with the balance of Davis’ Brigade, left southern Virginia to join the new division. The regiment would remain within this organizational structure (Davis’ Brigade, Heth’s Division, Hill’s Third Corps, Army of Northern Virginia) for the remainder of the war.[6] [1] Joseph H. Crute, Jr., Units of the Confederate States Army (Midlothian, VA, 1987), pp. 187-188, 239; Stewart Sifakis, Compendium of the Confederate Armies: Mississippi (New York, 1995), pp. 133-134, North Carolina, pp. 155-156; InfoConcepts, Inc., The American Civil War Regimental Information System: Volume I --the Confederates (Albuquerque, 1994, 1995), computer database software. [2] O.R., 19, pt. 2, p. 705. [3] O.R., 18, p. 883; Mark M. Boatner, III, The Civil War Dictionary (New York, 1991), p. 817. [4] Ibid.; Steven A. Cormier, The Siege of Suffolk: The Forgotten Campaign, April 11-May 4, 1863 (Lynchburg, VA, 1989), 246-248. [5] Stephen W. Sears, Chancellorsville (Boston, 1996), pp. 117-121, 293-297, 446-448. [6] Ray F. Sibley, Jr. The Confederate Order of Battle: The Army of Northern Virginia, Volume 1, (Shippensburg, 1996), p. 52; O.R., 27, pt. 3, p. 860. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: South Mountain and Antietam  Colonel Evander Law Colonel Evander Law The usually cautious McClellan’s newfound sense of aggressiveness was fostered by the discovery on September 13th of a copy of Lee’s campaign plans outlining the division of the Confederate army and routes of march. On September 14th, the Army of the Potomac engaged the Southern forces detached to guard passes through South Mountain, Maryland. Responding to the seriousness of the threat, Longstreet ordered Hood back from Hagerstown via Boonsboro to reinforce the Confederate defenders at Fox’s Gap. Immediately upon arriving, Hood deployed Law’s Brigade and his Texans, and in a counterattack, drove the Federals back at bayonet point. The 2nd Mississippi suffered approximately 17-18 casualties, mostly wounded and captured.[1] At nightfall, Lee fell back from the gaps with Hood’s Division acting as rear guard. Although a more prudent commander would have probably fallen back across the Potomac into Virginia, Lee chose to stand and fight. He concentrated his forces in a strong defensive position on the west side of Antietam Creek around the village of Sharpsburg, Maryland. He wanted to maintain this position to block any attempted advance by McClellan and allow time to complete the capture of Harpers Ferry and its garrison.[2] Tired and hungry, the men of the 2nd Mississippi found it necessary to again advance against the Federals at dusk on the evening of September 16th. Elements of the Army of the Potomac had crossed Antietam Creek north of Lee’s army and were moving into positions opposite the Confederate left flank. Hood was ordered into the East Woods, a small woodlot which was being infiltrated by Federal skirmishers. Law’s Brigade, in skirmish order just north of the East Woods, was suddenly met by a reconnaissance party of the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves (“Bucktails”). The Bucktails, with their Sharps breechloading rifles, used their enhanced firepower to turn the slow withdrawal of Law’s skirmishers into a stampede as they neared the edge of the woods. Luckily, the 4th and 5th Texas arrived to hit the Pennsylvanians simultaneously from the west and south, supported by a section of howitzers from Stephen D. Lee’s artillery battalion. By 8:00 p.m. however, most of Hood’s units had fallen back to the West Woods for the night. As darkness fell, Law’s Brigade soon came under Federal artillery fire from the batteries to their right on the other side of Antietam Creek.[3] As night approached, the men lay in the West Woods, facing north while the Union heavy guns fired down the length of their lines from the east. Luckily, most of the shots fell just in front or rear of the Confederate positions. However, the colonel of the 11th Mississippi, Phillip Liddell, was struck in the torso by a bursting shell fragment and would die two days later.[4] Sometime after midnight, Hood’s men were relieved and allowed to get some rest and food. Other than a half ration of beef and some green corn, they had not eaten for three days. As most of the men wearily returned to their original positions near the Dunker Church, details from each company were sent to forage for food and prepare a morning meal.[5] The men of the 2nd Mississippi were awakened on the morning of September 17th while it was still dark. Although Hood had persuaded General Lee to allow the division to stay in reserve long enough for the men to eat their long-overdue meal, McClellan’s battle plans did not cooperate. Shells began to fall near the Dunker Church in preparation for a Federal assault on the Confederate left. Law was forced to order the still-hungry men to fall into ranks and prepare for battle.[6] Somewhat after 6:00 a.m., Colonel Law moved his brigade in columns east across the Hagerstown Pike, where it turned north and deployed in a single battle line. The 2nd Mississippi under Colonel Stone anchored the extreme left of Law’s line, while next came the 11th Mississippi, 6th North Carolina and 4th Alabama on the extreme right. To the left of the 2nd Mississippi the Texas Brigade was similarly deployed in line, with the 1st Texas on the right of the brigade. Law’s men advanced into the Miller Cornfield in a generally northerly direction, loading and firing as they went, except for the 4th Alabama, which moved by the right flank down the Smoketown Road toward the East Woods. The veteran fighters of the 2nd and 11th Mississippi and the 6th North Carolina savagely drove the Federals out of the Cornfield (probably upset at having their long-anticipated breakfasts interrupted). They then reformed along a rail fence at the northern edge of the field, continuing to fire at Federal batteries and infantry units coming onto the scene. At one point, the Confederate line rose and fired at a mere thirty feet distance into the 4th and 8th Pennsylvania Reserves, panicking them, which in turn, panicked the 3rd Pennsylvania Reserves in their rear. As the Federals regrouped and additional reinforcements arrived, however, Hood’s men saw they could not continue to hold their position without help. Union soldiers were infiltrating the gap that had developed between the 6th North Carolina’s right flank and the 4th Alabama’s left, slowed by its advance into the East Woods. The men had to fall back. As Law’s men withdrew, the northern border of the Cornfield along the fence was marked by a long precise, row of Mississippians, stuck down where they stood by one terrible fire.[7] Hood’s punishing counterattack into the Miller Cornfield had saved the Confederate left, but at a terrible cost. As the survivors retired behind the Dunker Church, they found only about 700 unwounded men of approximately 2000 in the division who had advanced at dawn. For expediency, the remnants of Hood’s two brigades were reorganized in the field as two regiments. Despite the losses however, these veteran soldiers recovered sufficiently to be used to gather up stragglers from other units. By 1:00 p.m., Hood had been resupplied with ammunition and the men were ready for combat once again, but the main fighting had moved further down the line. The Federals showed no further interest in trying to advance against the Confederate left for the remainder of the day.[8] After the war, on June 1, 1876, Colonel Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin wrote Colonel (then Governor) Stone a letter that mentioned the fight at Antietam. It reads in part, “We fought the Second Mississippi in the corn field in front of the Dunkark [sic] Church at Antietam. They drove us, and we barely saved by hand a battery of six twelve-pound howitzers, planted in front of some hay stacks. You will remember this place well, if your [sic] are Col. Stone of that Regiment.” This would not be the last time the 2nd Mississippi encountered the 6th Wisconsin in battle. The regiment reported heavy losses of 27 killed and 127 wounded at Antietam. Its strength is not known with certainty, but may have numbered about 300 effectives at the start of the battle (most Southern regiments were much reduced by straggling on the march north into Maryland). Among the wounded were Colonel Stone, Lieutenant Colonel David Humphreys and Major John Blair, all the regiment’s field officers.[9] [1] CMSR. [2] Johnson and Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders, vol. 2, p. 603; O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 839, 922-923; pt. 2, pp. 609-610; Priest, Before Antietam, p. 218. [3] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 937; Priest, Antietam, pp. 15-17, 19-23. [4] Ibid., p. 18. Davis, Leaves in an Autumn Wind, p. 285. [5] Murfin, Bayonets, p. 210. [6] O.R., 19, pt. 1, p. 923, 937. [7] Priest, Antietam, pp. 52, 55-56, 61-62, 64-65, 68-70; Sears, Landscape, p. 213. [8] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 925, 938; Sears, Landscape, p. 276. [9] Rietti, Military Annals of Mississippi, p. 36; Rowland, Military History of Mississippi, p. 47. One of the wounded was the author’s great-grandfather, Private Thomas Benton Weatherington, Company H, 2nd Mississippi. His pension application says he was wounded in both legs on September 17. A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment: Second Manassas Following Malvern Hill, Hood’s Division recuperated in the vicinity of Richmond for several weeks. Concluding that Richmond was no longer in danger from McClellan’s forces still on the Peninsula, Lee decided that Major General John Pope, commander of the newly formed Federal Army of Virginia,[1] needed to be “suppressed.” On August 13, 1862, Hood was ordered north to take part in Lee’s new offensive. Lee hoped to strike Pope before the balance of McClellan’s troops could be brought back from the Peninsula as reinforcements. Lee sent Jackson around Pope’s right flank and followed with Longstreet’s command as the Federal commander “took the bait” and moved north in pursuit of Jackson.[2]

After destroying the Federal supply depot at Manassas on August 26th, Jackson established a defensive position along an unfinished railroad cut near the old Manassas battlefield. Pope, after finally locating Jackson, began launching attacks against the position on the evening of August 28th. At about 10:00 a.m. the following day, Lee and Longstreet joined Jackson, while Pope remained oblivious to their presence. Jackson’s men were exhausted and running critically low on ammunition. Longstreet advanced his wing northeasterly along the Warrenton Turnpike, Hood’s Division in the vanguard. Longstreet spent much of the day methodically deploying a massive assault column to smash into Pope’s left flank. Hood positioned his old Texas Brigade to the right of the turnpike and Law [click to read his official report] to the left. Law’s Brigade thus became the leftmost infantry command in Longstreet’s line, almost, but not quite, linking with Jackson’s right, the gap being covered by Confederate artillery.[3] About 6:00 p.m. Hood’s men were preparing to conduct a reconnaissance to their front, when two Federal brigades with attached artillery and cavalry, obviously unaware of a Confederate presence, came down the turnpike. Pope, who was convinced that Jackson was in retreat and ignorant of Longsteet’s arrival, had prematurely ordered a pursuit of the supposed retreating Confederates. Hood’s men ambushed the Federal column and pushed them back up the turnpike more than half a mile. At one point a Federal counterattack threatened to throw the Confederates back. Brigadier General Abner Doubleday’s Federal brigade was threatening to turn Law’s right flank. Law countered this move by aligning the 2nd Mississippi along the road, at right angles to the rest of his line. The Mississippians raked Doubleday’s men with an enfilading fire and forced them to retreat to the top of the ridge. As the Confederates continued to advance and engaged the Federals in the failing light atop the ridge, the fighting degenerated into a confused, bloody brawl. Finally however, the Confederates swept the remaining Union infantry and artillery off the ridge. By this time, only dead and wounded Federals remained. Doubleday’s and Colonel Timothy Sullivan’s (formerly Brigadier General John P. Hatch’s) Federal brigades had become a disorganized mob, heading rearward. Officers rode among the men, trying to rally them in hope that they might at least cover a retreat long enough so that some of the wounded could be brought off. After unsuccessfully berating several groups of retreating Federal troops, Major Charles Livingston of the 76th New York finally came across a regiment marching, as the Seventy-sixth’s historian put it, “in tolerable order.” Livingston ordered them to halt and turn about, “giving emphasis to the command by earnest gesticulations with his sword, and insisting that it was a shame to see a whole regiment running away.” An officer of the regiment in question, apparently annoyed that a stranger would presume to usurp his command, challenged Livingston: “Who are you sir?” The reply came back, “Major Livingston of the Seventy-sixth New York.” “Seventy-sixth what?” asked the officer. “Seventy-sixth New York.” “Well, then,” replied the officer, probably with more than a little bemused satisfaction, “you are my prisoner, for you are attempting to rally the Second Mississippi.”[4] As darkness fell and it was only with difficulty that friend could be distinguished from foe, Hood disengaged and fell back to his original position. By midnight, the 2nd Mississippi was back in line just north of the Warrenton Turnpike near the Brawner Farm.[5] With the morning of August 30th, Lee awaited Pope’s renewed attacks. However Pope spent the morning arguing with his subordinates that the Confederates were in retreat and not, as was actually the case, massing for a counterstroke. Finally at 3:00 p.m. Porter’s V Corps launched a final attack on Jackson’s position, allowing Longstreet’s artillery to pour a deadly enfilade fire into the left flank of the assault column. The Federal attack swept from southeast to northwest diagonally across the front of Hood’s Division. During this final Federal attack, the men of Hood’s division were essentially just spectators. Finally, Longstreet, seeing that Porter’s attack had been repulsed and that Pope had committed his reserves, sent his own massive assault column of 25,000 gray infantry forward, Hood’s Division in the lead, in a smashing counterattack.[6] With Hood’s Division designated the “column of direction” for Longstreet’s assault, Law, in theory, was to have advanced on the Texas Brigade’s left flank, just north of the turnpike. Theory had long since fallen victim to dust, death and confusion, however. Law lost contact with the Texans almost immediately. His advance instead amounted to a series of moves from one rise to the next in support of some of Hood’s batteries. By about 5:30 p.m. Law had worked his brigade into position in some timber along Young’s Branch at the base of Dogan Ridge. On the ridge above them, Law’s men could see what was left of Major General Franz Sigel’s Union corps, along with a number of batteries, including Captain Hubert Dilger’s, which had proven to be a particular annoyance to the Southerners during their advance. Law decided to attack. Although successful in putting the 45th New York Infantry Regiment to flight, Law’s pursuit was checked by the 2nd and 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments – Iron Brigade units – backed by artillery. Thinking this was a situation his brigade should not tackle alone, Colonel Law decided to break off the engagement and return to the base of the ridge.[7] The 2nd Mississippi reported losses of 22 killed and 87 wounded for the two days of fighting. Its strength at Second Manassas was not reported, but the regiment may have carried as many as 450-500 men into action.[8] The beaten Army of Virginia limped back to Washington where it was absorbed into the Army of the Potomac, once more under McClellan’s helm. Lee now decided to take the fight north into Maryland. Potential foreign recognition, fresh recruits from pro-Southern Marylanders, and improved subsistence for the army from Maryland’s unravaged countryside all played a part in the decision to launch his raid. The Army of Northern Virginia left the vicinity of Manassas on September 2nd, crossed the Potomac north of Leesburg, and on September 7th occupied Frederick, Maryland. Lee decided to split his forces in order to capture the large Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry. The bulk of Longstreet’s troops, including the 2nd Mississippi, marched west to Hagerstown while Jackson’s men with assorted other army detachments took various roads south. Shortly after their arrival at Hagerstown, word came that McClellan had left Washington and was uncharacteristically pressing aggressively upon Lee’s rear guard and screening forces.[9] [1] The army was created by combining the three Federal commands that Jackson had bested during his Shenandoah Valley Campaign – the commands of Shields, Banks and Fremont. [2] O.R., 11, pt. 3, p. 675; John J. Hennessy, Return to Bull Run (New York, 1993), pp. 138-139, 144-146, 163. [3] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 605; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 289-290. [4] Ibid., pp. 295-296, 298-299. The 2nd Mississippi officer in question was not identified. [5] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 623; Hennessy, Bull Run, p. 303. [6] O.R., 12, pt. 2, pp. 565-566; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 339-342, 350-351, 362-365. [7] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 624; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 425-426; David G. Martin, The Second Bull Run Campaign (Conshohocken, 1997), pp. 246-247. [8]O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 625. CMSR. [9] O.R., 19, pt. 1, p. 839, 922, pt. 2, p. 183, 590-592, 603-604; James V. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets (Baton Rouge, 1965), pp. 88-90; John Michael Priest, Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle (New York, 1989), p. xxiii; Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (Boston, 1983), pp. 63-67, 90-92. CMSR. Few new recruits joined the regiment following the spring of 1862. |

Michael R. BrasherBesides being the self-published author of Civil War books, I am the great-grandson of Private Thomas Benton Weatherington, one of the 1,888 Confederate soldiers from northeast Mississippi that served in the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. A lifelong Civil War buff, I grew up near the Shiloh battlefield in West Tennessee. I received my MA in Civil War Studies from American Military University. I also hold degrees in Electrical Engineering and an MBA which I draw upon to help shape my own unique approach to researching and writing Civil War history. As former president and co-founder of InfoConcepts, Inc., I was the co-developer of the American Civil War Regimental Information System and Epic Battles of the American Civil War software. I developed and maintained the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment website from 2002 until 2015 and now maintain the 2nd Mississippi Facebook page. I am also writing a regimental history to be released in the near future. I am a retired Air Force officer and now reside in Huntsville, Alabama. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed